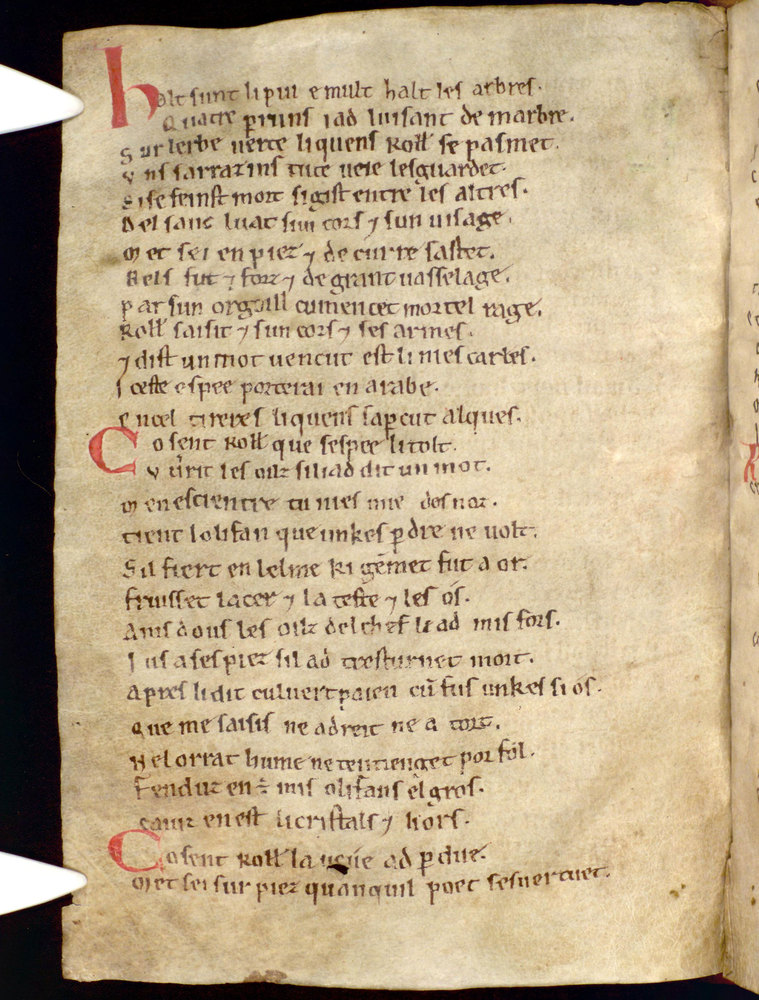

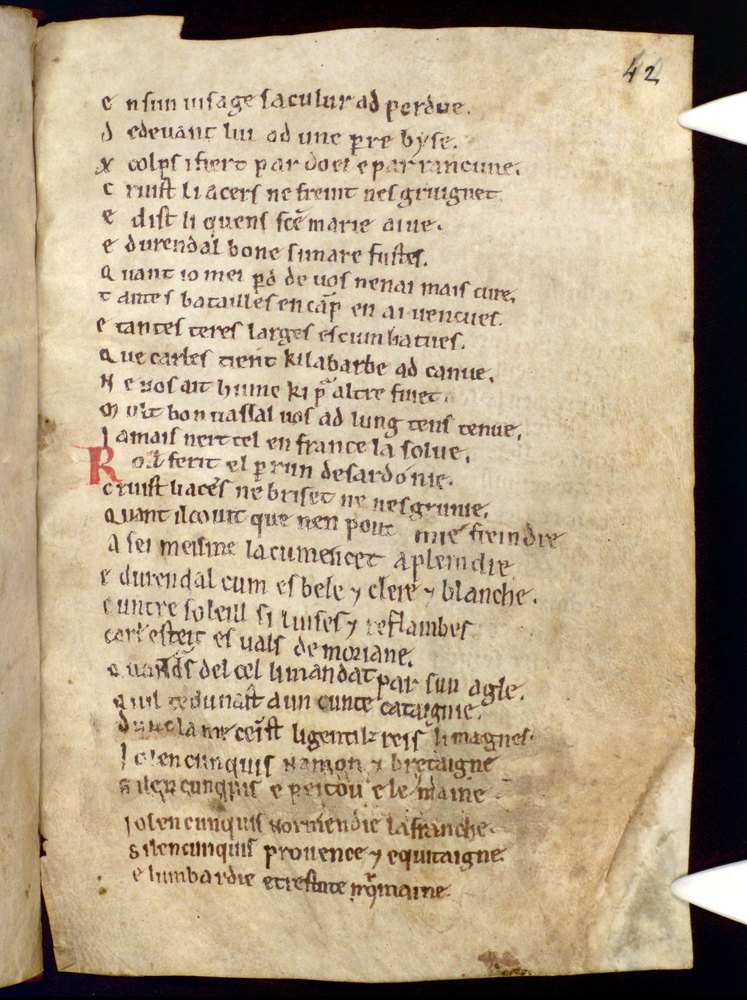

Chanson de Roland

This Treasure is paired with: Earliest surviving book printed in Oxford (Oxford's early books)

Knowing that death is near, Roland tries to break his sword Durendal, so that it cannot be used by the enemy. The great epic of early French literature is shown here in its oldest surviving manuscript. It was almost certainly copied in England around the second quarter of the 12th century, and bequeathed to Oxford’s Oseney Abbey in the 13th century, providing evidence for Oxford’s long-standing role as a repository for books.

Translation

171

Now Roland feels his sight grow dim and weak;

With his last strength he struggles to his feet;

All the red blood has faded from his cheeks.

A grey stone stands before him at his knee:

Ten strokes thereon he strikes, with rage and grief;

It grides, but yet nor breaks nor chips the steel.

‘Ah!’ cries the Count, ‘St Mary succour me!

Alack the day, Durendal, good and keen!

Now I am dying, I cannot fend for thee.

How many battles I’ve won with you in field!

With you I’ve conquered so many goodly fiefs

That Carlon holds, the lord with the white beard!

Let none e’er wield you that from the foe would flee –

You that were wielded so long by a good liege!

The like of you blest France shall never see.’

172

Count Roland smites the sardine stone amain.

The steel grides loud, but neither breaks nor bates.

Now when he sees that it will nowise break

Thus to himself he maketh his complaint:

‘Ah, Durendal! so bright, so brave, so gay!

How dost thou glitter and shine in the sun’s rays!

When Charles was keeping the vales of Moriane,

God by an angel sent to him and ordained

He should bestow thee on some count-capitayne.

From The Song of Roland, trans. Dorothy L Sayers (London, 1957), p. 139-140. © Dorothy L Sayers, 1957. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd.

This Treasure isn’t currently on display in the Weston Library.